“The pleasure of the Text also includes the amicable return of the author. Of course, the author who returns is not the one identified by our institutions; he is not even the biographical hero. The author who leaves his text and comes into our life has no unity; he is a mere plural of ‘charms,’ the site of a few tenuous details, yet the course of vivid novelistic glimmerings, a discontinuous chant of amiabilities, in which we nevertheless read breadth more certainly than in the epic of a fate; he is not a (civil, moral) person, he is a body…

Were I a writer, and dead, how I would love it if my life, through the pains of some friendly and detached biographer, were to reduce itself to a few details, a few preferences, a few inflections, let us say: to ‘biographemes’ whose distinction and mobility might go beyond any fate and come to touch, like Epicurean atoms, some future body, destined to the same dispersion…”

—Barthes, Sade, Fourier, Loyola

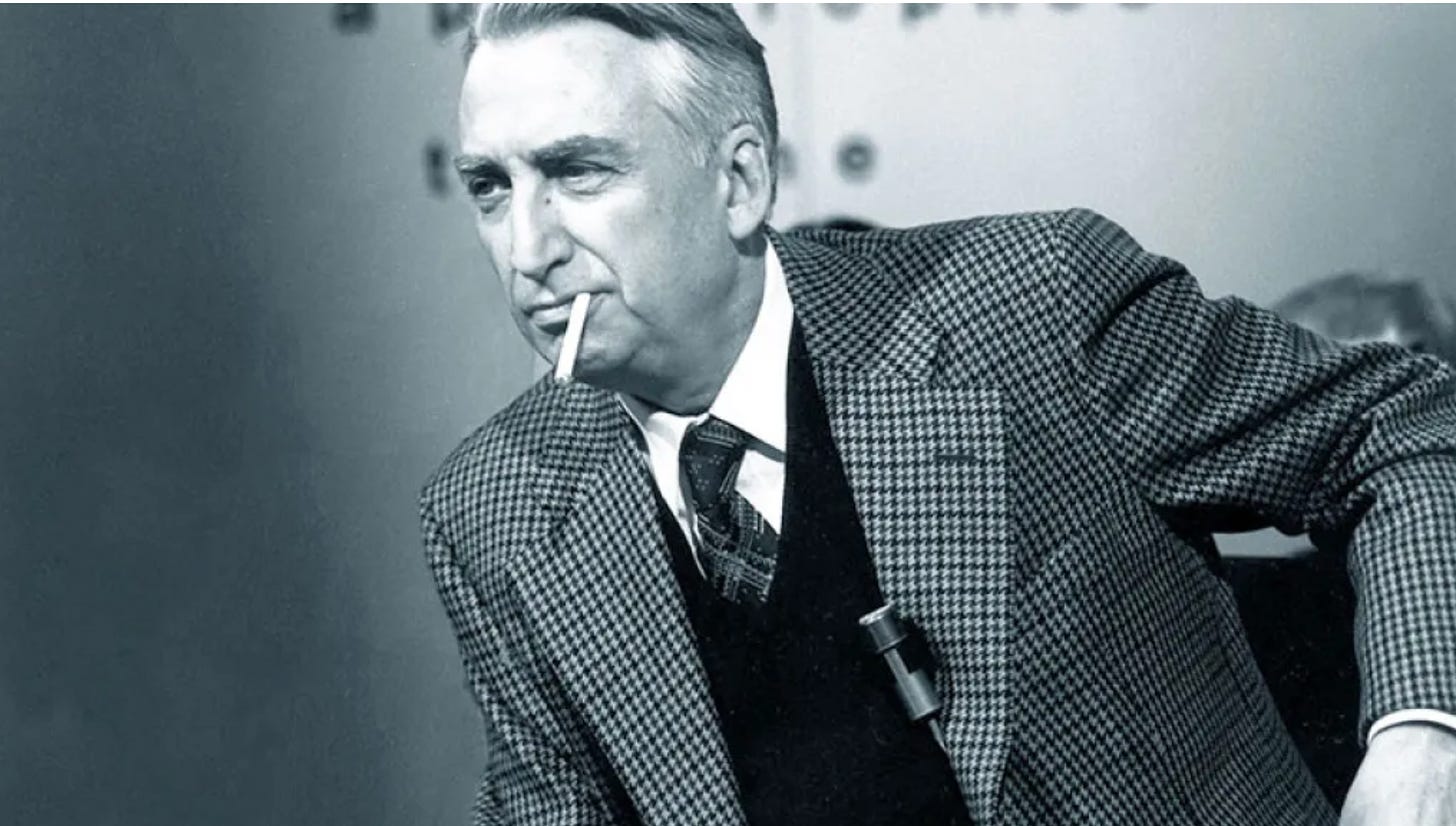

I first heard that the author was dead in my second or third week of college. His demise was mentioned offhandedly, at the end of a meandering seminar monologue, by a junior literature major with whom I was already miserably in love. We’ll call her B. I don’t remember which author was killed on that September afternoon, but I remember waiting for B outside the classroom afterwards, staring at a stain in the carpet while she chatted with the professor. I remember the way my voice cracked (actually cracked) when she came through the door, and I asked “Wha-at did you mean by tha-at? Do you really believe intention doesn’t ma-atter?” And I remember watching her perfectly scuffed Doc Martens appear and disappear under the hem of her skirt as we walked from the Humanities building to the Dining Hall and she taught me to roll the r’s in “Roland Barthes.”

By the time we reached the all-day omelette station in the cafeteria, B had mentioned no fewer than 6 times that she had a boyfriend, and I had decided to take French. I was furious when I found out that the essay from which the phrase “death of the author” came was only about 6 pages long. “You can’t just throw out thousands of years of common sense in 1500 words.” She wasn’t interested in arguing.

Still, Roland made some good points. Maybe the author really was a “modern figure,” a joint product of the Reformation, British empiricism, French rationalism, capitalism, and English teachers. As a Catholic School Boy at a Small Liberal Arts College (TM), I already knew that none of the above could be trusted. I was more skeptical of the claim “Mallarmé was doubtless the first to see and foresee in its full extent the necessity of substituting language itself for the man who hitherto was supposed to own it,” because I had never heard of Mallarmé, and this seemed like too important an event for me to be unaware of it. If the author really was dead, and somebody named Mallarmé had killed him, and nobody ever told me about it, that would be like if every high school in America had conspired to cover up World War I.

Next stop: office hours, and a very patient Assistant Professor who was definitely not teaching this Introduction to Poetry course by choice. He offered the rough explanation that I’ve since repeated to dozens of my own students: The Author is not the causal agent of the Text. It is wrong to see the source the Text in the personal life of the writer, in his Unique Experience or in his individual “Genius.” As critics, we ought to think of the Author as really just the point through which various social discourses pass; he or she assembles words on the page, in a certain order, according to certain unconscious rules of syntax and narrative, within the limits of what is thinkable by a given social milieu. “Sure, sure. Okay. Makes sense. Sure. But isn’t the author intending to connect these words in a certain way?”

Luckily, this Assistant Professor did not want to spend the rest of the semester arguing about free will and determinism with a teenager. Story old as time. “Look, the ‘death of the author’ is a kind of slogan. It’s an analytical strategy, it just means that the intentions of the author aren’t the relevant object of analysis. Your job isn’t to imagine how Faulkner or O’Connor felt when they said this, or why they believed it. Your job is to tell me what the text says, and how it works. The rest is biography.”

“The rest is biography.” At the time, I took that to mean that biography was a lesser art—not even an art, more like a kind of journalism—an embarrassing and vaguely seedy practice of accumulating gossip about Hemingway’s mistresses and Duras’s drinking problems. I was resentful, too, because I only had days before come up with the brilliant idea of becoming a biographer, after realizing that my lack of imagination meant I was never going to be much of a novelist. “The story’s already there, you just need to tell it,” I had written in a notebook. “More money in it too, maybe.”

About six months later (and this will surprise nobody), I was enrolled in an independent study on Derrida and Blanchot with that same Assistant Professor, while also preparing for a summer language course in France. Post-structuralism is a hell of a drug, especially when mixed with teenaged longing.

I tell this story because I think it’s a near-universal experience of self-serious English Majors who came of age between the ‘90s and the ‘10s. I probably caught the tail end of it, thanks to being at a small college with a large French department and a lot of Gen X professors who had been raised on structuralism and its discontents. They were, I will note, uniformly suspicious of these new-fangled “Digital Humanities” and “New Materialisms,” the Big Ideas of which all seemed to have been simultaneously formulated and debunked by Derrida and Foucault already anyway.

The experience I’m talking about is the experience of Theory, with a capital T—the first encounter with some grand philosophical claim, the evisceration of common sense, the rush of a run-on sentence collapsing into a stream of semi-colons and neologisms; the frisson of finally grasping the sense of one of those neologisms, not after 3 careful re-reads of the sentence but on the very first try; the sense not so much that the Big Questions had been answered, but that new ones could be asked and that I suddenly had permission not to be burdened by them anymore, to bracket them, or to simply leave them behind like friends at a party.

My enthusiasm for post-structuralism would ultimately lead me through Marxism, through psychoanalysis, through Lukacs and Sartre and Frankfurt and Althusser and Jameson, as well as to somewhat embarrassing but no less formative detours of Mark Fisher, Zizek, and a certain kind of Deleuze (you know the one I mean). But it started, for me as for so many of my “contemporaries”—a term I find myself using more and more often as I get older and some of those classmates and dorm-mates make real names for themselves while I dither around on Twitter—with Barthes.

And when I think of Barthes, I don’t lose much sleep anymore over the ontological consequences of his account of the subject, or whatever. I think of his sentences, of how reading them at first felt like peeling the skin off a clove of garlic with wet fingers, the way that phrases would stick stubbornly to my brain and slip away at the same time.

I think of how, when I came across the concept of “marking” I thought not of the signifying chain but of the scuff marks on B’s Doc Martens. I think of how, when Barthes imagines a few inconsequential details of his life traversing the void of his death and swerving deliciously into the consciousness of some future reader like Epicurean atoms, he remains too modest (and too clever) to enumerate any of those perfect, crystalline details for us.

Great story. Not sure if you had it in mind but very relevant to the recent Sinykin/Lorentzen debate and the resulting discussion around genius…

This brought back memories for me of my time at University in 1980. Post-structuralism was the big ticket then! And didn't we all have a 'B' we fell in love with?! Thanks for sharing!