The dead are not dead, and they are hungry. They live together in hotels and other transitory sites, invisible to the living except at certain angles. Some spend their days debating the ontological status of their existence, its consequences for whatever counted as knowledge on the other side of the big sleep. Others look for ways out—some back into the land of the living, some into a more complete annihilation. And still others endlessly replay and analyze the few remaining fragments of memory from their lives: the loss of a child, the dialogue from Moonstruck, one perfect day making love in the California dunes. All of them are hungry, maddeningly hungry, and spend their nights eating the flesh of the living.

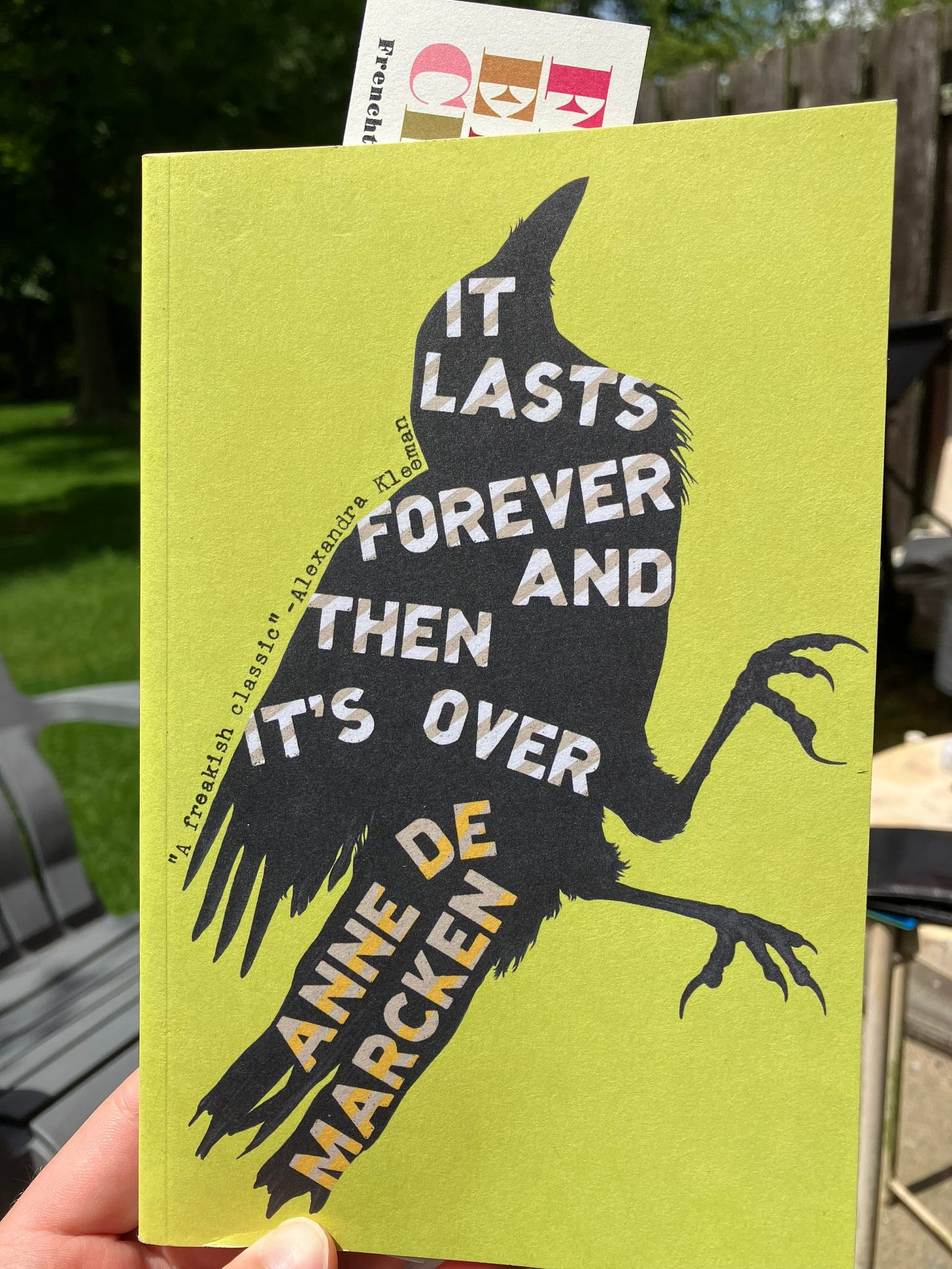

The narrator of Anne de Marcken’s first novel, It Lasts Forever and Then Its Over, which won the Novel Prize and was published simultaneously by New Directions, Fitzcarraldo, and Giramodo in 2024, has lost an arm. She carries it with her for a while, caressing it in bed like a lover, before cremating it. She finds a crow in the street, wraps it in a Juicy sweatshirt, and sews it inside herself. The crow speaks to her, a series of concrete and abstract nouns without any obvious connection. “Apple. Arm. Ink. Crown.” And so on. We experience this parataxis as alternately oracular and nonsensical, each word exerting a kind of spooky causality on all the others that mirrors and intensifies the dream-logic of the novel’s plot. She and we cannot help but feel addressed by the crow, and she will ultimately come to believe she has interpreted some message from the static, though we never learn its content.

Things accelerate once the narrator decides to stop eating. She has killed a teenaged girl and experienced something like a shock of recognition. But the decision to stop eating is not moral. It’s more like an attempt to bow out of the game she’s been playing since arriving at the hotel. “We are just like the living. Hunger is only ravenous hope. A mirage. Always receding. The black swarm behind my teeth. There is no bottom to this well. No dark place to wait it out. Nothing will ever touch this craving for you. How long before we let ourselves know what we know?” Hunger is hope because each meal offers the false promise of final satisfaction, the return of the lost object that we know but cannot admit will never return to us, will never make us whole.

Over the course of the novel, we gain little insight into this “you” addressed throughout. A lover left behind, the paradigm for a lost object, inflated into a totem that constitutes the narrator’s primary connection to her old life. If hunger is hope, and hope is satisfaction, and satisfaction is a dream of return to something ever-receding, then the narrator’s longing for this “you” is coextensive with her violence towards the living. Each victim is a stand-in for the lost object. She must give up one to give up the other.

What little we do hear of the you is recounted in fragments of encounter, experiences the two shared. One recurs throughout the novel, the sight of a swam of bees in a tree:

“It was solid and liquid and crawling and black and shimmering. iT was the body of one thing made out of the bodies of other things. One animal made out of other animals. It was a shimmering black octopus made of bees. Dripping bees. It kept reshaping itself into a new octopus. Bulbous head and webbed body and tentacles. It was horrifying and beautiful. That’s what’s inside of me. Only instead of an octopus, it is hunger. Instead of bees, it is made of nothing. Hunger is an animal made of nothing.”

Shades of Sartre’s great passages in Nausea, describing the gnarled root of the chestnut tree—its “soft, monstrous masses, all in disorder—naked, in a fright, obscene nakedness”—and Roquentin’s decisive identification with that obscenity, that disorder. Says Roquentin: I, like this tree and like every object in the world, am strange, unlikely, disordered, subject to contingency, thrown into the world and hurled out of it. “We were a heap of creatures, irritated, embarrassed at ourselves, we hadn’t the slightest reason to be there… And all these existents which bustled about this tree came from nowhere and were going nowhere.” And my only comfort is that I too am nothing, that my coming from nowhere renders me both one with the world and radically apart from it—engulfed within it, but nonetheless absurdly free.

De Marcken’s narrator assumes her own freedom by refusing the game of hunger—choosing simply to suffer the pangs without satisfying them, no matter how extreme they become. But she does not give up on her experience, on the continuation of her undead life. One fellow-undead, named Marguerite, tries to end her suspended existence by burning herself in a pyre, an act which may or may not end up destroying the world. A dark void opens up and swallows everything it can, while the narrator runs beyond the hotel, beyond the city limits, out towards the West, trying to reach the dunes where she once made love.

On this journey, it becomes clear that her object is no longer a reuniting with her lover, not a rediscovery of the object lost, not an act of hope. It is, instead, a dream to return with a difference to the scene of a single perfect day, a year before her death. The lover is reduced in her memory to the memory of that day, shared between without mutual intrusion, but with a gentle intensity and something like an aesthetic perfection. She finds her friends from the hotel, reborn somewhere in the midwest and wearing Pirates jerseys, with new names, different but the same. She is captured, beheaded, and crucified by a post-apocalyptic cult—then released by an old woman who takes pity.

She walks the rest of the distance to the ocean, holding her head in her hands, an acéphalic embodiment of drive. The entire novel is dripping with more psychoanalytic imagery—Lacanian and Bataillean in equal measure—than I can unpack here after a single read. Her body walks into the sea while her head remains on the shore, and the final reflections take on the enigmatic-orphic power of the crow’s initial words:

“When you have arrived at the thing itself, then all you can do is compare is to something else you don’t understand. A rock, a crow. The only things that remain themselves are the ones you can enter reach. The things that are too big or too far away or move too slowly to detect. Smooth. Feathered. Loved. Already lost. They will always be only what they really are, and you will never know what name to call out to them.

I am on the ocean, I am on the shore. I am trying to remember or to see.

The space between me and me is you. This is a mystery.”

The things of the world are what they are—massive, simple, singular. Comparison belongs to language, and the recognition of language’s inadequacy cannot stop the human need to compare, to explain, to think one thing in terms of another. The meaning is therefore never in any particular object but in the space between the thing and its other, in the comparison itself. What meaning there is for us belongs to metaphor, but every metaphor is itself an attempt to abolish the metaphoric. Death is the great Thing that is not a thing, and therefore the paradigm case of the Thing. A site of non-being that we can never experience but can only think as an accumulation of absences—a world without a world.

But I too cannot be myself, I too am what I am and—tragically, miraculously—what I am not. There is a space between me and me: between the totality of my experience (my memory, my history, my absences) and that which I am, that which not only bears the first me on its back like a turtle but which is the condition of possibility for any me at all. Life consists in the relation between them, and that relation is nothing but “you.” You, the other, my particular other, the loss that is my own, addressed and absent, grieved without hope, as much a mystery to yourself as you are to me.